KNXlock Update August 2023

Recent scans from Alpha Strike Labs show that there are still more than 16,000 potentially vulnerable systems in the DACH area. Although we reported this attack campaign in late 2021, we are still receiving attack reports in 2023. Therefore the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency CISA released a new security advisory about KNXlock including a new CVE.

As a consequence of this attack, a new attack technique was added in spring 2023 to the MITRE ATT&CK framework for industrial control system: T0892, titled “change credential“.

In October 2021 we received an interesting request for help from a German engineering company. The company, providing electrical and automation engineering services for various industrial cases was having an issue with one of their customers: They had been contracted at some point to engineer the building automation system of a mid-sized site. They built the system based on the so-called KNX technology, which is a building automation standard that is very common throughout Europe. KNX is a very powerful standard, as it allows to engineer and manage everything from small to very large building sites.

The problem the engineering company was facing, could be easily described:

Someone had gotten access to their building automation control system over the internet and locked the owners out of it. The building contained several hundred of KNX components and ¾ of them were no longer operational due to the attack.

Control system devices which are publicly accessible on the internet have been a known problem that security experts were pointing for a decade already. What made this attack campaign interesting was that it was executed, using unique, control system-technology specific aspects.

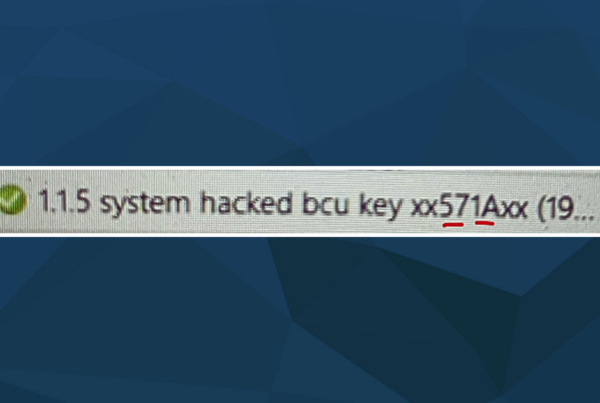

It was not as sophisticated and damaging as the attack campaigns with Stuxnet, Industroyer or Trisis, which were conducted much more comprehensively. Quite contrary the attackers just needed to understand specifics of KNX technology and how specific features could be abused. One specific function was very important among others for the attack: In KNX, it is possible to set a so-called bus coupling unit (BCU) key, which was designed as a protective function into the standard, to prevent unwanted changes to the devices.

When a BCU Key is set, all the KNX devices in the engineered project that support this feature, will be locked during the engineering process using a password (8 characters or 4 Bytes long). Once enabled, devices protected with a BCU key therefore cannot be changed afterwards unless the password is known. Although different implementations exists, most devices will not allow a reset of the password, even with physical access to the device.

The attackers understood obviously how to abuse specific functions of KNX, as after gaining access, they firstly unloaded the devices and then set the BCU key on those devices. This is the equivalent of first purging the hard disk of a computer and then setting a password on the hard disk. The computer can be switched on, but it’s not doing anything useful anymore as it has lost its operating system and applications. And without that password, no operating system or application may be installed on the hard disk anymore, leaving the computer “dumb”.

Hundreds of control devices compromised

The real-world result of this attack was that hundreds of building automation control devices were not working anymore. Consequently, what had been a smart building before, had lost its smartness completely, as its brains and nervous system was missing. But also simple devices and processes were not accessible anymore including light switches and shutter control. The engineer claimed that as a last resort they had been operating the entire building on manual mode, some components getting rewired to be operated via circuit breaker or other means of centralised, manual control.

The engineering company started looking for help externally, finding ways of regaining access and control to their building control system. They initially reached out to the most logical party in the industrial supply chain: The device vendors. Multiple building automation vendors were contacted, asking them for help or a way to reset the password to regain access.

All vendors unfortunately claimed that no reset was possible, and all devices were considered to be bricked. The suggestion was the equipment should be completely ripped and replaced. This would have cost over hundred thousand euros considering hardware, installation and verification costs. Therefore, the engineers were looking for other, less costly options of recovery.

Thomas Brandstetter had been giving a talk titled “(in)security in building automation: How to create dark buildings with light speed” at Black Hat USA 2017. In his presentation, he was describing how KNX and BACnet, two key technology standards in the building automation space, could be misused by attackers. The presentation was available online, where it was found by the engineering company, which then contacted Limes Security.

”“Although I had predicted this in my Black Hat Talk in 2017, I was struck hearing that someone now was conducting attacks against sector-specific control systems abusing application-level technology functions. This was obviously no University lab, but the real world, and you can’t just easily reset or rip and replace an entire building control system, at least not at low cost. Luckily, the presentation helped some of the victims find their way to us so we could try to help them.

Thomas Brandstetter

How we fixed it

And the help worked out: Several compromised devices were sent to Limes Security and analyzed for potential ways to recover the keys. The first check was to verify if there is really no pre-determined way for resetting the devices, which unfortunately could quickly be confirmed. Two security specialists from Limes Security, Peter Panholzer and Felix Eberstaller, formed a team to search for ways how to recover the key. Bruteforcing was the first obvious idea, was however quickly discarded, as it would potentially take several years due to the slow response of the devices to authentication attempts. This could only work if the number of potential keys could be reduced. Several other ideas were discussed and discarded. They then attempted to read out the memory directly from the CPUs on the devices. This works only if there is no protection set on the CPUs which was the case for some but not all devices. We used this weakness to dump the memory which at that point is only a huge pile of unidentified bits and bytes. So we were still looking almost literally for the needle in the hay stack (pun intended!). Long story short: Instead of debugging or reverse engineering the memory content, which is a long and cumbersome task, we came up with an idea to limit the area in the pile of bits and bytes where the key would most likely be stored. Almost like we (hopefully) found the right handful of hay from the stack. With the remaining possible bytes that could include the password, we got back to the brute forcing idea and voila – could finally identify the password which was then returned to the system integrator who could then re-gain access to the building automation control system, re-do the engineering, and make the building smart again. The recovery worked and the building could get fully operational again.

Was this cyber-vandalism?

What the reason and goal of the adversary was is unknown at this point, as no ransom request was received by the operator owning the system. This may have been just an advanced act of cyber-vandalism, or maybe just the practical difficulty to find out over the Internet who the operator of that system really is” and where to address the ransom note to.

”Many people don’t realize how complex and powerful some control system protocols actually are. In the hand of a knowledgeable attacker, this power may of course be turned against the operator as well, if they gain access to a device. This, as many control systems in use today still lack basic security functions, because they were designed at a time when security was not considered a necessity yet. That’s why we have to make sure those devices aren’t easily accessible to adversaries.

Thomas Brandstetter

Details about the attack methodology and recovery approach will be presented by Peter Panholzer, one of the lead experts working on this case, at the S4X22 conference in Miami, end of January.

Read more about the KNXlock incident on Dark Reading: